Dialect continuum

This article needs additional citations for verification. (May 2016) |

| Part of a series on |

| Linguistics |

|---|

|

|

A dialect continuum or dialect chain is a series of language varieties spoken across some geographical area such that neighboring varieties are mutually intelligible, but the differences accumulate over distance so that widely separated varieties may not be.[1] This is a typical occurrence with widely spread languages and language families around the world, when these languages did not spread recently. Some prominent examples include the Indo-Aryan languages across large parts of India, varieties of Arabic across north Africa and southwest Asia, the Turkic languages, the varieties of Chinese, and parts of the Romance, Germanic and Slavic families in Europe. Terms used in older literature include dialect area (Leonard Bloomfield)[2] and L-complex (Charles F. Hockett).[3]

Dialect continua typically occur in long-settled agrarian populations, as innovations spread from their various points of origin as waves. In this situation, hierarchical classifications of varieties are impractical. Instead, dialectologists map variation of various language features across a dialect continuum, drawing lines called isoglosses between areas that differ with respect to some feature.[4]

A variety within a dialect continuum may be developed and codified as a standard language, and then serve as an authority for part of the continuum, e.g. within a particular political unit or geographical area. Since the early 20th century, the increasing dominance of nation-states and their standard languages has been steadily eliminating the nonstandard dialects that comprise dialect continua, making the boundaries ever more abrupt and well-defined.

Dialect geography

[edit]

Dialectologists record variation across a dialect continuum using maps of various features collected in a linguistic atlas, beginning with an atlas of German dialects by Georg Wenker (from 1888), based on a postal survey of schoolmasters. The influential Atlas linguistique de la France (1902–10) pioneered the use of a trained fieldworker.[5] These atlases typically consist of display maps, each showing local forms of a particular item at the survey locations.[6]

Secondary studies may include interpretive maps, showing the areal distribution of various variants.[6] A common tool in these maps is an isogloss, a line separating areas where different variants of a particular feature predominate.[7]

In a dialect continuum, isoglosses for different features are typically spread out, reflecting the gradual transition between varieties.[8] A bundle of coinciding isoglosses indicates a stronger dialect boundary, as might occur at geographical obstacles or long-standing political boundaries.[9] In other cases, intersecting isoglosses and more complex patterns are found.[10]

Relationship with standard varieties

[edit]

Standard varieties may be developed and codified at one or more locations in a continuum until they have independent cultural status (autonomy), a process the German linguist Heinz Kloss called ausbau. Speakers of local varieties typically read and write a related standard variety, use it for official purposes, hear it on radio and television, and consider it the standard form of their speech, so that any standardizing changes in their speech are towards that variety. In such cases the local variety is said to be dependent on, or heteronomous with respect to, the standard variety.[12]

A standard variety together with its dependent varieties is commonly considered a "language", with the dependent varieties called "dialects" of the language, even if the standard is mutually intelligible with another standard from the same continuum.[13][14] The Scandinavian languages, Danish, Norwegian and Swedish, are often cited as examples.[15] Conversely, a language defined in this way may include local varieties that are mutually unintelligible, such as the German dialects.[16]

The choice of standard is often determined by a political boundary, which may cut across a dialect continuum. As a result, speakers on either side of the boundary may use almost identical varieties, but treat them as dependent on different standards, and thus part of different "languages".[17] The various local dialects then tend to be leveled towards their respective standard varieties, disrupting the previous dialect continuum.[18] Examples include the boundaries between Dutch and German, between Czech, Slovak and Polish, and between Belarusian and Ukrainian.[19][20]

The choice may be a matter of national, regional or religious identity, and may be controversial. Examples of controversies are regions such as the disputed territory of Kashmir, in which local Muslims usually regard their language as Urdu, the national standard of Pakistan, while Hindus regard the same speech as Hindi, an official standard of India. Even so, the Eighth Schedule to the Indian Constitution contains a list of 22 scheduled languages and Urdu is among them.

During the time of the former Socialist Republic of Macedonia, a standard was developed from local varieties of Eastern South Slavic, within a continuum with Torlakian to the north and Bulgarian to the east. The standard was based on varieties that were most different from standard Bulgarian. Now known as Macedonian, it is the national standard of North Macedonia, but viewed by Bulgarians as a dialect of Bulgarian.[21]

Europe

[edit]

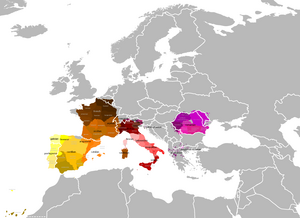

Europe provides several examples of dialect continua, the largest of which involve the Germanic, Romance and Slavic branches of the Indo-European language family, the continent's largest language branches.

The Romance area spanned much of the territory of the Roman Empire but was split into western and eastern portions by the Slav Migrations into the Balkans in the 7th and 8th centuries.

The Slavic area was in turn split by the Hungarian conquest of the Carpathian Basin in the 9th and 10th centuries.

Germanic languages

[edit]

North Germanic continuum

[edit]The Norwegian, Danish and Swedish dialects comprise a classic example of a dialect continuum, encompassing Norway, Denmark, Sweden and coastal parts of Finland. The Continental North Germanic standard languages (Norwegian, Danish and Swedish) are close enough and intelligible enough for some [who?] to consider them to be dialects of the same language, but the Insular ones (Faroese and Icelandic) are not immediately intelligible to the other North Germanic speakers.

Continental West Germanic continuum

[edit]Historically, the Dutch, Frisian, Low Saxon and High German dialects formed a canonical dialect continuum, which has been gradually falling apart since the Late Middle Ages due to the pressures of modern education, standard languages, migration and weakening knowledge of the dialects.[27]

The transition from German dialects to Dutch variants followed two basic routes:

- From Central German to Southeastern Dutch (Limburgish) in the so-called Rhenish fan, an area corresponding largely to the modern Niederrhein in which gradual but geographically compact changes took place.[28]

- From Low Saxon[b] to Northwestern Dutch (Hollandic): This sub-continuum also included West Frisian dialects up until the 17th century, but faced external pressure from Standard Dutch and, after the collapse of the Hanseatic League, from Standard German which greatly influenced the vocabularies of these border dialects.[27]

Though the internal dialect continua of both Dutch and German remain largely intact, the continuum which historically connected the Dutch, Frisian and German languages has largely disintegrated. Fragmentary areas of the Dutch-German border in which language change is more gradual than in other sections or a higher degree of mutual intelligibility is present still exist, such as the Aachen-Kerkrade area, but the historical chain in which dialects were only divided by minor isoglosses and negligible differences in vocabulary has seen a rapid and ever-increasing decline since the 1850s.[27]

Standard Dutch was based on the dialects of the principal Brabantic and Hollandic cities. The written form of Standard German originated in the East Central German used at the chancery of the kingdom of Saxony, while the spoken form emerged later, based on North German pronunciations of the written standard.[29] Being based on widely separated dialects, the Dutch and German standards do not show a high degree of mutual intelligibility when spoken and only partially so when written. One study concluded that, when concerning written language, Dutch speakers could translate 50.2% of the provided German words correctly, while the German subjects were able to translate 41.9% of the Dutch equivalents correctly. In terms of orthography, 22% of the vocabulary of Dutch and German is identical or near-identical.[30][31]

Anglic continuum

[edit]The Germanic dialects spoken on the island of Great Britain comprise areal varieties of English in England and of Scots in Scotland. Those of large areas north and south of the border are often mutually intelligible. In contrast, the Orcadian dialect of Scots is very different from the dialects of English in southern England—but they are linked by a chain of intermediate varieties.

Romance languages

[edit]Western Romance continuum

[edit]

The western continuum of Romance languages comprises, from West to East: in Portugal, Portuguese; in Spain, Galician, Leonese or Asturian, Castilian or Spanish, Aragonese and Catalan or Valencian; in France, Occitan, Franco-Provençal, standard French and Corsican which is closely related to Italian; in Italy, Ligurian, Piedmontese, Lombard, Emilian, Romagnol, Italian Gallo-Picene, Venetian, Friulian, Ladin; and in Switzerland, Lombard and Romansh. This continuum is sometimes presented as another example, but the major languages in the group (i.e. Portuguese, Spanish, French and Italian) have had separate standards for longer than the languages in the Continental West Germanic group, and so are not commonly classified as dialects of a common language.

Focusing instead on the local Romance lects that pre-existed the establishment of national or regional standard languages, all evidence and principles point to Romania continua as having been, and to varying extents in some areas still being, what Charles Hockett called an L-complex, i.e. an unbroken chain of local differentiation such that, in principle and with appropriate caveats, intelligibility (due to sharing of features) attenuates with distance. This is perhaps most evident today in Italy, where, especially in rural and small-town contexts, local Romance is still often employed at home and work, and geolinguistic distinctions are such that while native speakers from any two nearby towns can understand each other with ease, they can also spot from linguistic features that the other is from elsewhere.

In recent centuries, the intermediate dialects between the major Romance languages have been moving toward extinction, as their speakers have switched to varieties closer to the more prestigious national standards. That has been most notable in France,[citation needed] owing to the French government's refusal to recognise minority languages,[32] but it has occurred to some extent in all Western Romance speaking countries. Language change has also threatened the survival of stateless languages with existing literary standards, such as Occitan.

The Romance languages of Italy are a less arguable example of a dialect continuum. For many decades since Italy's unification, the attitude of the French government towards the ethnolinguistic minorities was copied by the Italian government.[33][34]

Eastern Romance continuum

[edit]The eastern Romance continuum is dominated by Romanian. Outside Romania and Moldova, across the other south-east European countries, various Romanian language groups are to be found: pockets of various Romanian and Aromanian subgroups survive throughout Bulgaria, Serbia, North Macedonia, Greece, Albania and Croatia (in Istria).

Slavic languages

[edit]Conventionally, on the basis of extralinguistic features (such as writing systems or the former western frontier of the Soviet Union), the North Slavic continuum is split into East and West Slavic continua. From the perspective of linguistic features alone, only two Slavic (dialect) continua can be distinguished, namely North and South,[35][36][37] separated from each other by a band of non-Slavic languages: Romanian, Hungarian and German.

North Slavic continuum

[edit]The North Slavic continuum covers the East Slavic and West Slavic languages. East Slavic includes Russian, Belarusian, Rusyn and Ukrainian; West Slavic languages of Czech, Polish, Slovak, Silesian, Kashubian, and Upper and Lower Sorbian. Eastern Slovak and Pannonian Rusyn stand out as sharing features with Slovak, Polish and Rusyn, thus serving as a transition between West and East Slavic languages.

South Slavic continuum

[edit]

All South Slavic languages form a dialect continuum.[38][39] It comprises, from West to East, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Serbia, North Macedonia, and Bulgaria.[40][41] Standard Slovene, Macedonian, and Bulgarian are each based on a distinct dialect, but the Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, and Serbian standard varieties of the pluricentric Serbo-Croatian language are all based on the same dialect, Shtokavian.[42][43][44] Therefore, Croats, Serbs, Bosniaks and Montenegrins communicate fluently with each other in their respective standardized varieties.[45][46][47] In Croatia, native speakers of Shtokavian may struggle to understand distinct Kajkavian or Chakavian dialects, as might the speakers of the two with each other.[48][49] Likewise in Serbia, the Torlakian dialect differs significantly from Standard Serbian. Serbian is a Western South Slavic standard, but Torlakian is largely transitional with the Eastern South Slavic languages (Bulgarian and Macedonian). Collectively, the Torlakian dialects with Macedonian and Bulgarian share many grammatical features that set them apart from all other Slavic languages, such as the complete loss of its grammatical case systems and adoption of features more commonly found among analytic languages.

The barrier between East South Slavic and West South Slavic is historical and natural, caused primarily by a one-time geographical distance between speakers. The two varieties started diverging early on (c. 11th century CE) and evolved separately ever since without major mutual influence, as evidenced by distinguishable Old Slavonic, while the western dialect of common Old Slavic was still spoken across the modern Serbo-Croatian area in the 12th and early 13th centuries. An intermediate dialect linking western and eastern variations inevitably came into existence over time – Torlakian – spoken across a wide radius on which the tripoint of Bulgaria, North Macedonia and Serbia is relatively pivotal.

Uralic languages

[edit]The other major language family in Europe besides Indo-European are the Uralic languages. The Sami languages, sometimes mistaken for a single language, are a dialect continuum, albeit with some disconnections like between North, Skolt and Inari Sami. The Baltic-Finnic languages spoken around the Gulf of Finland form a dialect continuum. Thus, although Finnish and Estonian are considered as separate languages, there is no definite linguistic border or isogloss that separates them. This is now more difficult to recognize because many of the intervening languages have declined or become extinct.

Goidelic continuum

[edit]The Goidelic languages consist of Irish, Scottish Gaelic and Manx. Prior to the 19th and 20th centuries, the continuum existed throughout Ireland, the Isle of Man and Scotland.[50][51] Many intermediate dialects have become extinct or have died out leaving major gaps between languages such as in the islands of Rathlin, Arran or Kintyre[52] and also in the Irish counties of Antrim, Londonderry and Down.

The current Goidelic speaking areas of Ireland are also separated by extinct dialects but remain mutually intelligible.

Middle East

[edit]Arabic

[edit]Arabic is a standard case of diglossia.[53] The standard written language, Modern Standard Arabic, is based on the Classical Arabic of the Qur'an, while the modern vernacular dialects (or languages) branched from ancient Arabic dialects, from North Western Africa through Egypt, Sudan, and the Fertile Crescent to the Arabian Peninsula and Iraq. The dialects use different analogues from the Arabic language inventory and have been influenced by different substrate and superstrate languages. Adjacent dialects are mutually understandable to a large extent, but those from distant regions are more difficult to be understood.[54]

The difference between the written standard and the vernaculars is apparent also in the written language, and children have to be taught Modern Standard Arabic in school to be able to read it.

Aramaic

[edit]All modern Aramaic languages descend from a dialect continuum that historically existed through the Aramaization of the Levant (other than the original Aramaic-speaking parts) and Mesopotamia[55] and before the Arabization of the Levant and Mesopotamia. Northeastern Neo-Aramaic, including distinct varieties spoken by both Jews and Christians, is a dialect continuum although greatly disrupted by population displacement during the twentieth century.[56][57][58]. The dialect continuum also includes Western Neo-Aramaic as spoken by Muslims and Christians in Syria.

Persian

[edit]The Persian language in its various varieties (Tajiki and Dari), is representative of a dialect continuum. The divergence of Tajik was accelerated by the shift from the Perso-Arabic alphabet to a Cyrillic one under the Soviets. Western dialects of Persian show greater influence from Arabic and Oghuz Turkic languages,[citation needed] but Dari and Tajik tend to preserve many classical features in grammar and vocabulary. [citation needed] Also the Tat language, a dialect of Persian, is spoken in Azerbaijan.

Turkic

[edit]Turkic languages are best described as a dialect continuum.[59] Geographically this continuum starts at the Balkans in the west with Balkan Turkish, includes Turkish in Turkey and Azerbaijani language in Azerbaijan, extends into Iran with Azeri and Khalaj, into Iraq with Turkmen, across Central Asia to include Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, to southern Regions of Tajikistan and into Afghanistan. In the south, the continuum starts in northern Afghanistan, northward to Chuvashia. In the east it extends to the Republic of Tuva, the Xinjiang autonomous region in Western China with the Uyghur language and into Mongolia with Khoton. The entire territory is inhabited by Turkic speaking peoples. There are three varieties of Turkic geographically outside the continuum: Chuvash, Yakut and Dolgan. They have been geographically separated from the other Turkic languages for an extensive period of time, and Chuvash language stands out as the most divergent from other Turkic languages.

There are also Gagauz speakers in Moldavia and Urum speakers in Georgia.

The Turkic continuum makes internal genetic classification of the languages problematic. Chuvash, Khalaj and Yakut are generally classified as significantly distinct, but the remaining Turkic languages are quite similar, with a high degree of mutual intelligibility between not only geographically adjacent varieties but also among some varieties some distance apart.[citation needed] Structurally, the Turkic languages are very close to one another, and they share basic features such as SOV word order, vowel harmony and agglutination.[60]

Indo-Aryan languages

[edit]Many of the Indo-Aryan languages of the Indian subcontinent form a dialect continuum. What is called "Hindi" in India is frequently Standard Hindi, the Sanskritized register of the colloquial Hindustani spoken in the Delhi area, the other register being Urdu. However, the term Hindi is also used for the different dialects from Bihar to Rajasthan and, more widely, some of the Eastern and Northern dialects are sometimes grouped under Hindi.[citation needed] The Indo-Aryan Prakrits also gave rise to languages like Gujarati, Assamese, Maithili, Bengali, Odia, Nepali, Marathi, Konkani and Punjabi.

Chinese

[edit]

Chinese consists of hundreds of mutually unintelligible local varieties.[61][62] The differences are similar to those within the Romance languages, which are similarly descended from a language spread by imperial expansion over substrate languages 2000 years ago.[63] Unlike Europe, however, Chinese political unity was restored in the late 6th century and has persisted (with interludes of division) until the present day. There are no equivalents of the local standard literary languages that developed in the numerous independent states of Europe.[64]

Chinese dialectologists have divided the local varieties into a number of dialect groups, largely based on phonological developments in comparison with Middle Chinese.[65] Most of these groups are found in the rugged terrain of the southeast, reflecting the greater variation in this area, particularly in Fujian.[66][67] Each of these groups contains numerous mutually unintelligible varieties.[61] Moreover, in many cases the transitions between groups are smooth, as a result of centuries of interaction and multilingualism.[68]

The boundaries between the northern Mandarin area and the central groups, Wu, Gan and Xiang, are particularly weak, due to the steady flow of northern features into these areas.[69][70] Transitional varieties between the Wu, Gan and Mandarin groups have been variously classified, with some scholars assigning them to a separate Hui group.[71][72] The boundaries between Gan, Hakka and Min are similarly indistinct.[73][74] Pinghua and Yue form a dialect continuum (excluding urban enclaves of Cantonese).[75] There are sharper boundaries resulting from more recent expansion between Hakka and Yue, and between Southwestern Mandarin and Yue, but even here there has been considerable convergence in contact areas.[76]

Cree and Ojibwa

[edit]Cree is a group of closely related Algonquian languages that are distributed from Alberta to Labrador in Canada. They form the Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi dialect continuum, with around 117,410 speakers. The languages can be roughly classified into nine groups, from west to east:

- Plains Cree (y-dialect)

- Woods Cree or Woods/Rocky Cree (ð-dialect)

- Swampy Cree (n-dialect)

- Eastern Swampy Cree

- Western Swampy Cree

- Moose Cree (l-dialect)

- East Cree or James Bay Cree (y-dialect)

- Northern East Cree

- Southern East Cree

- Atikamekw (r-dialect)

- Western Montagnais (l-dialect)

- Innu-aimun or Eastern Montagnais (n-dialect)

- Naskapi (y-dialect)

Various Cree languages are used as languages of instruction and taught as subjects: Plains Cree, Eastern Cree, Montagnais, etc. Mutual intelligibility between some dialects can be low. There is no accepted standard dialect.[77][78][79]

Ojibwa (Chippewa) is a group of closely related Algonquian languages in Canada, which is distributed from British Columbia to Quebec, and the United States, distributed from Montana to Michigan, with diaspora communities in Kansas and Oklahoma. With Cree, the Ojibwe dialect continuum forms its own continuum, but the Oji-Cree language of this continuum joins the Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi dialect continuum through Swampy Cree. The Ojibwe continuum has 70,606 speakers. Roughly from northwest to southeast, it has these dialects:

- Ojibwa-Ottawa

- Algonquin

- Oji-Cree (Northern Ojibwa) or Severn

- Ojibwa

- Western Ojibwa or Saulteaux

- Chippewa (Southwestern Ojibwa)

- Northwestern Ojibwa

- Central Ojibwa or Nipissing

- Eastern Ojibwa or Mississauga

- Ottawa (Southeastern Ojibwa)

- Potawatomi

Unlike the Cree–Montagnais–Naskapi dialect continuum, with distinct n/y/l/r/ð dialect characteristics and noticeable west–east k/č(ch) axis, the Ojibwe continuum is marked with vowel syncope along the west–east axis and ∅/n along the north–south axis.

See also

[edit]- A language is a dialect with an army and navy (an aphorism spread among linguists)

- Dialect, including the classification units "dialect cluster", "language cluster" and "dialect group"

- Dialect levelling

- Dialectometry

- Diasystem

- Diglossia

- Koine language

- Language secessionism

- Linkage (linguistics)

- Macrolanguage

- Post-creole speech continuum

- Ring species, an analogous concept in ecology

Notes

[edit]- ^ Carpathian Ruthenia is mistakenly excluded from North Slavic on the map, even though Rusyn, an East Slavic dialect group on the transition to West Slavic, is spoken there.

- ^ In this context, "A group of related dialects of Low German, spoken in northern Germany and parts of the Netherlands, formerly also in Denmark." (Definition from Wiktionary)

References

[edit]- ^ Crystal, David (2006). A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics (6th ed.). Blackwell. p. 144. ISBN 978-1-405-15296-9.

- ^ Bloomfield, Leonard (1935). Language. London: George Allen & Unwin. p. 51.

- ^ Hockett, Charles F. (1958). A Course in Modern Linguistics. New York: Macmillan. pp. 324–325.

- ^ Chambers, J.K.; Trudgill, Peter (1998). Dialectology (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 13–19, 89–91. ISBN 978-0-521-59646-6.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), pp. 15–17.

- ^ a b Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 25.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 27.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), pp. 93–94.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), pp. 94–95.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), pp. 91–93.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 10.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), pp. 9–12.

- ^ Stewart, William A. (1968). "A sociolinguistic typology for describing national multilingualism". In Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.). Readings in the Sociology of Language. De Gruyter. pp. 531–545. doi:10.1515/9783110805376.531. ISBN 978-3-11-080537-6.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 11.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), pp. 3–4.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 4.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 9.

- ^ Woolhiser, Curt (2011). "Border effects in European dialect continua: dialect divergence and convergence". In Kortmann, Bernd; van der Auwera, Johan (eds.). The Languages and Linguistics of Europe: A Comprehensive Guide. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 501–523. ISBN 978-3-11-022025-4. p. 501.

- ^ Woolhiser (2011), pp. 507, 516–517.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (1997). "Norwegian as a Normal Language". In Røyneland, Unn (ed.). Language Contact and Language Conflict. Volda College. pp. 151–158. ISBN 978-82-7661-078-9. p. 152.

- ^ Trudgill, Peter (1992). "Ausbau sociolinguistics and the perception of language status in contemporary Europe". International Journal of Applied Linguistics. 2 (2): 167–177. doi:10.1111/j.1473-4192.1992.tb00031.x. pp. 173–174.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 6.

- ^ W. Heeringa: Measuring Dialect Pronunciation Differences using Levenshtein Distance. University of Groningen, 2009, pp. 232–234.

- ^ Peter Wiesinger: Die Einteilung der deutschen Dialekte. In: Werner Besch, Ulrich Knoop, Wolfgang Putschke, Herbert Ernst Wiegand (Hrsg.): Dialektologie. Ein Handbuch zur deutschen und allgemeinen Dialektforschung, 2. Halbband. de Gruyter, Berlin / New York 1983, ISBN 3-11-009571-8, pp. 807–900.

- ^ Werner König: dtv-Atlas Deutsche Sprache. 19. Auflage. dtv, München 2019, ISBN 978-3-423-03025-0, pp. 230.

- ^ C. Giesbers: Dialecten op de grens van twee talen. Radboud Universiteit Nijmegen, 2008, pp. 233.

- ^ a b c Niebaum, Herman (2008). "Het Oostnederlandse taallandschap tot het begin van de 19de eeuw". In Van der Kooij, Jurgen (ed.). Handboek Nedersaksische taal- en letterkunde. Van Gorcum. pp. 52–64. ISBN 978-90-232-4329-8. p. 54.

- ^ Chambers & Trudgill (1998), p. 92.

- ^ Henriksen, Carol; van der Auwera, Johan (1994). König, Ekkehard; van der Auwera, Johan (eds.). The Germanic Languages. Routledge. pp. 1–18. ISBN 978-0-415-05768-4. p. 11.

- ^ Gooskens, Charlotte; Kürschner, Sebastian (2009). "Cross-border intelligibility – on the intelligibility of Low German among speakers of Danish and Dutch" (PDF). In Lenz, Alexandra N.; Gooskens, Charlotte; Reker, Siemon (eds.). Low Saxon dialects across borders – Niedersächsische Dialekte über Grenzen hinweg. Stuttgart: Steiner. pp. 273–295. ISBN 978-3-515-09372-9.

- ^ Gooskens & Heeringa (2004)

- ^ "Le Sénat dit non à la Charte européenne des langues régionales". Franceinfo. 27 October 2015. Archived from the original on 3 December 2023.

- ^ "Italy : 5.1 General legislation : 5.1.9 Language laws". Compendium of Cultural Policies and Trends in Europe. Council of Europe/ERICarts. 18 September 2013. Archived from the original on 2 March 2014. Retrieved 26 February 2014.

- ^ Cerruti, Massimo (26 January 2011). "Italiano e dialetto oggi in Italia". Treccani. Archived from the original on 23 October 2022.

- ^ Peter Trudgill. 2003. A Glossary of Sociolinguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, pp 36, 95-96, 124-125.

- ^ [1]Tomasz Kamusella. 2017. Map A4, Dialect Continua in Central Europe, 1910 (p 94) and Map A5, Dialect Continua in Central Europe, 2009 (p 95). In: Tomasz Kamusella, Motoki Nomachi, and Catherine Gibson, eds. 2017. Central Europe Through the Lens of Language and Politics: On the Sample Maps from the Atlas of Language Politics in Modern Central Europe (Ser: Slavic Eurasia Papers, Vol 10). Sapporo, Japan: Slavic-Eurasian Research Center, Hokkaido University.

- ^ Kamusella, Tomasz (2005). "The Triple Division of the Slavic Languages: A Linguistic Finding, a Product of Politics, or an Accident?" (Working Paper). Vienna: Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen. 2005/1.

- ^ Crystal, David (1998) [1st pub. 1987]. The Cambridge encyclopedia of language. Cambridge, New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 25. OCLC 300458429.

- ^ Friedman, Victor (1999). Linguistic emblems and emblematic languages: on language as flag in the Balkans. Kenneth E. Naylor memorial lecture series in South Slavic linguistics; vol. 1. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University, Dept. of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures. p. 8. OCLC 46734277.

- ^ Alexander, Ronelle (2000). In honor of diversity: the linguistic resources of the Balkans. Kenneth E. Naylor memorial lecture series in South Slavic linguistics; vol. 2. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio State University, Dept. of Slavic and East European Languages and Literatures. p. 4. OCLC 47186443.

- ^ Kristophson, Jürgen (2000). "Vom Widersinn der Dialektologie: Gedanken zum Štokavischen" [Nonsense of Dialectology: Thoughts on Shtokavian]. Zeitschrift für Balkanologie (in German). 36 (2): 180. ISSN 0044-2356.

- ^ Kordić, Snježana (2004). "Pro und kontra: "Serbokroatisch" heute" [Pros and cons: "Serbo-Croatian" today] (PDF). In Krause, Marion; Sappok, Christian (eds.). Slavistische Linguistik 2002: Referate des XXVIII. Konstanzer Slavistischen Arbeitstreffens, Bochum 10.-12. September 2002 (PDF). Slavistishe Beiträge; vol. 434 (in German). Munich: Otto Sagner. pp. 97–148. ISBN 978-3-87690-885-4. OCLC 56198470. SSRN 3434516. CROSBI 430499. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 9 March 2017.

- ^ Blum, Daniel (2002). Sprache und Politik : Sprachpolitik und Sprachnationalismus in der Republik Indien und dem sozialistischen Jugoslawien (1945–1991) [Language and Policy: Language Policy and Linguistic Nationalism in the Republic of India and the Socialist Yugoslavia (1945–1991)]. Beiträge zur Südasienforschung; vol. 192 (in German). Würzburg: Ergon. p. 200. ISBN 978-3-89913-253-3. OCLC 51961066.

- ^ Gröschel, Bernhard (2009). Das Serbokroatische zwischen Linguistik und Politik: mit einer Bibliographie zum postjugoslavischen Sprachenstreit [Serbo-Croatian Between Linguistics and Politics: With a Bibliography of the Post-Yugoslav Language Dispute]. Lincom Studies in Slavic Linguistics; vol 34 (in German). Munich: Lincom Europa. pp. 82–83. ISBN 978-3-929075-79-3. LCCN 2009473660. OCLC 428012015. OL 15295665W.

- ^ Kordić, Snježana (2010). Jezik i nacionalizam [Language and Nationalism] (PDF). Rotulus Universitas (in Croatian). Zagreb: Durieux. pp. 74–77. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3467646. ISBN 978-953-188-311-5. LCCN 2011520778. OCLC 729837512. OL 15270636W. CROSBI 475567. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 June 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Pohl, Hans-Dieter (1996). "Serbokroatisch – Rückblick und Ausblick" [Serbo-Croatian – Looking backward and forward]. In Ohnheiser, Ingeborg (ed.). Wechselbeziehungen zwischen slawischen Sprachen, Literaturen und Kulturen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart : Akten der Tagung aus Anlaß des 25jährigen Bestehens des Instituts für Slawistik an der Universität Innsbruck, Innsbruck, 25–27 Mai 1995. Innsbrucker Beiträge zur Kulturwissenschaft, Slavica aenipontana; vol. 4 (in German). Innsbruck: Non Lieu. pp. 205–219. OCLC 243829127.

- ^ Šipka, Danko (2019). Lexical layers of identity: words, meaning, and culture in the Slavic languages. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 166. doi:10.1017/9781108685795. ISBN 978-953-313-086-6. LCCN 2018048005. OCLC 1061308790. S2CID 150383965.

lexical differences between the ethnic variants are extremely limited, even when compared with those between closely related Slavic languages (such as standard Czech and Slovak, Bulgarian and Macedonian), and grammatical differences are even less pronounced. More importantly, complete understanding between the ethnic variants of the standard language makes translation and second language teaching impossible", leading Šipka "to consider it a pluricentric standard language

- ^ Škiljan, Dubravko (2002). Govor nacije: jezik, nacija, Hrvati [Voice of the Nation: Language, Nation, Croats]. Biblioteka Obrisi moderne (in Croatian). Zagreb: Golden marketing. p. 12. OCLC 55754615.

- ^ Thomas, Paul-Louis (2003). "Le serbo-croate (bosniaque, croate, monténégrin, serbe): de l'étude d'une langue à l'identité des langues" [Serbo-Croatian (Bosnian, Croatian, Montenegrin, Serbian): from the study of a language to the identity of languages]. Revue des études slaves (in French). 74 (2–3): 315. ISSN 0080-2557.

- ^ Mac Eoin, Gearóid (1993). "Irish". In Ball, Martin J. (ed.). The Celtic Languages. London: Routledge. pp. 101–44. ISBN 978-0-415-01035-1.

- ^ McManus, Damian (1994). "An Nua-Ghaeilge Chlasaiceach". In K. McCone; D. McManus; C. Ó Háinle; N. Williams; L. Breatnach (eds.). Stair na Gaeilge in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta (in Irish). Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp. 335–445. ISBN 978-0-901519-90-0.

- ^ McLeod, Wilson (2017). "Dialectal diversity in contemporary Gaelic: perceptions, discourses and responses" (PDF). University of Aberdeen. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 February 2022.

- ^ Wahrmund, Adolf (1898). Praktisches Handbuch der neu-arabischen Sprache ... Vol. 1-2 of Praktisches Handbuch der neu-arabischen Sprache (3 ed.). J. Ricker. Retrieved 6 July 2011.

- ^ Kaye, Alan S.; Rosenhouse, Judith (1997). "Arabic Dialects and Maltese". In Hetzron, Robert (ed.). The Semitic Languages. Routledge. pp. 263–311. ISBN 978-0-415-05767-7.

- ^ Bunnens, Guy (2009). "ASSYRIAN EMPIRE BUILDING AND ARAMIZATION OF CULTURE AS SEEN FROM TELL AHMAR/TIL BARSIB". Syria. Institut Francais du Proche-Orient.

- ^ Kim, Ronald (2008). ""Stammbaum" or Continuum? The Subgrouping of Modern Aramaic Dialects Reconsidered". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 128 (3): 505–531. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 25608409.

- ^ Mutzafi, Hezy (23 August 2018). "Further Jewish Neo-Aramaic Innovations". Journal of Jewish Languages. 6 (2): 145–181. doi:10.1163/22134638-06011130. ISSN 2213-4638. S2CID 165973597.

- ^ Khan, Geoffrey (2020). "The Neo-Aramaic Dialects of Iran". Iranian Studies. 53 (3–4): 445–463. doi:10.1080/00210862.2020.1714430. S2CID 216353456.

- ^ Grenoble, Lenore A. (2003). Language policy in the Soviet Union. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. ISBN 0-306-48083-2. OCLC 53984252.

- ^ Grenoble, Lenore A. (2003). Language Policy in the Soviet Union. Vol. 3. Springer-Verlag. ISBN 978-1-4020-1298-3.

- ^ a b Norman, Jerry (2003). "The Chinese dialects: phonology". In Thurgood, Graham; LaPolla, Randy J. (eds.). The Sino-Tibetan languages. Routledge. pp. 72–83. ISBN 978-0-7007-1129-1. p. 72.

- ^ Hamed, Mahé Ben (2005). "Neighbour-nets portray the Chinese dialect continuum and the linguistic legacy of China's demic history". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1567): 1015–1022. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.3015. JSTOR 30047639. PMC 1599877. PMID 16024359.

- ^ Norman, Jerry (1988). Chinese. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 187. ISBN 978-0-521-29653-3.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 2–3.

- ^ Kurpaska, Maria (2010). Chinese Language(s): A Look Through the Prism of "The Great Dictionary of Modern Chinese Dialects". Walter de Gruyter. pp. 41–55. ISBN 978-3-11-021914-2.

- ^ Ramsey, S. Robert (1987). The Languages of China. Princeton University Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-0-691-01468-5.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 183–190.

- ^ Sagart, Laurent (1998). "On distinguishing Hakka and non-Hakka dialects". Journal of Chinese Linguistics. 26 (2): 281–302. JSTOR 23756757. p 299.

- ^ Norman (1988), pp. 190, 206–207.

- ^ Halliday, M.A.K (1968) [1964]. "The users and uses of language". In Fishman, Joshua A. (ed.). Readings in the Sociology of Language. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 139–169. ISBN 978-3-11-080537-6. p. 12.

- ^ Yan, Margaret Mian (2006). Introduction to Chinese Dialectology. LINCOM Europa. pp. 223–224. ISBN 978-3-89586-629-6.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 206.

- ^ Norman (1988), p. 241.

- ^ Norman (2003), p. 80.

- ^ de Sousa, Hilário (2016). "Language contact in Nanning: Nanning Pinghua and Nanning Cantonese". In Chappell, Hilary M. (ed.). Diversity in Sinitic Languages. Oxford University Press. pp. 157–189. ISBN 978-0-19-872379-0. p. 162.

- ^ Halliday (1968), pp. 11–12.

- ^ "LINGUIST List 6.744: Cree dialects". www.linguistlist.org. 29 May 1995.

- ^ "Canada".

- ^ "Cree Language and the Cree Indian Tribe (Iyiniwok, Eenou, Eeyou, Iynu, Kenistenoag)". www.native-languages.org. Archived from the original on 4 April 2011. Retrieved 10 September 2008.